A HOME OF OUR OWN, Part 1

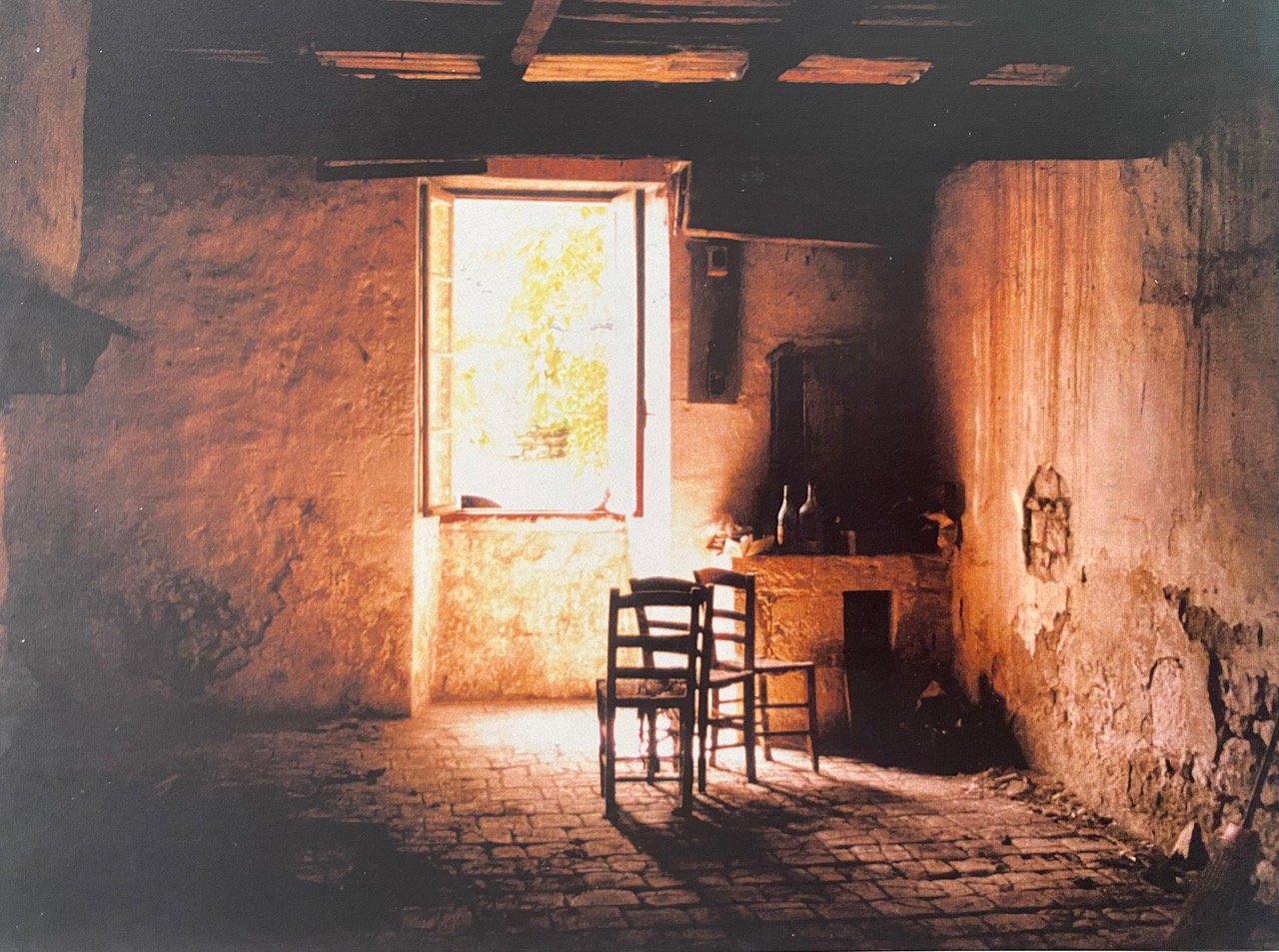

A small photo sat on my desk for fifteen years, tucked between constantly updated ones of my two kids. It is a corner of a room, mostly in shadow. Through a narrow window, light streams onto cracked terracotta floors. Two battered wooden chairs with frayed cane seats are the room’s only furniture. The photo is of the ruin my husband and I bought in the south of France. Our ruin is small but substantial, with stonewalls a meter thick. The pigeonnier (dovecote) dates from the late 17th century. The attached barn was built 100 or so years later, a few years before the French Revolution. We bought the pigeonnier first, from a middle-aged man who had inherited it from his uncle. The pigeonnier had no electricity or running water. His uncle had lived, the nephew told us, comme autrefois, (like in the old days). He drank water pumped from the well and ate meals cooked in the fireplace. He slept when it was dark and with the livestock, when it was cold.

We met the nephew at the agence immoblier, (real estate agency) the August evening we bought his uncle’s home. Despite a cool breeze outside, the tiny windowless back office where we sat on sticky plastic chairs around a rickety plastic table, was stifling hot. It was our last night in the Dordogne. We were leaving for Paris and then home to San Francisco the next morning. We had hoped to come in, sign a purchase agreement and leave. Wishful thinking. Orchestrated by the real estate agent and a friend of his who spoke some English, the nephew, my husband and I initialed, signed, dated and wrote ‘lu et approuve’ (read and approved) on a dizzying number of pages. Two hours later, sweaty and exhausted, we signed the last sheet of the final document and shook hands. “Au revoir et bon retour” (Goodbye and have a safe trip home) the nephew shouted over his shoulder as he hurried out. He had already alerted us that he was under a time constraint. He didn’t want to miss his favorite television show, reruns of ”Les Rues de San Francisco.”

We had come to the Dordogne for two reasons that year (1989). To see as many exhibitions commemorating the French Revolution as we could. And to buy a house. Two years earlier, my husband and I, with our baby daughter, had visited the region for the first time. It was the last stop on our two month long trip home after five years in Australia. Good years during which my husband was part of the architectural team that designed and oversaw the building of Australia’s New Parliament House and I taught art history at the Australian National University. And our dual nationality daughter was born.

After stops in Phuket and Bangkok, Santorini and Athens, we spent two weeks in Tuscany – two weeks during which the sun never shone and the temperature never rose above a chilling 50 degrees. Two weeks during which we were always arriving just as a store was closing or a restaurant’s lunch service was ending. All that changed when we reached the Perigord. That first morning, in Bergerac, we woke up and gazed from our hotel room window at a vast Farmers Market spread out in the square below. After years in Australia and weeks in Italy, we knew better than to risk any store being opened between Saturday at noon and Monday at 3:00p.m. We loaded the car with fruit and vegetables and drove an hour to St Marcel du Perigord and the gite that was our home for the next 14 days. For two weeks, we almost always seemed to arrive at whatever town or village I had selected to visit when its Farmers Market was in full throttle. The weather was almost always a deliciously warm 70 degrees, and the sky was almost always a robin’s egg blue.

The one time it did rain, the three of us were back in Bergerac. Caught off guard, we found shelter under the awning of a building. Bored with watching the rain fall, my husband had turned around. After a few minutes, he nudged me. The window behind us was filled with rows of fuzzy photos of houses for sale. I mentally did the conversion from francs to dollars.

When we returned to San Francisco, my husband and I began house hunting. With our combined salaries as underpaid architect and under-employed art historian, it soon became clear that homeownership in San Francisco was unlikely. I began having nightmares about being old and poor and maybe sick and homeless in San Francisco. The more I thought about it, the more buying a home in the South of France seemed like a prudent idea. Indeed, the only sensible thing to do. After all, if we couldn’t afford San Francisco while we were working, how would we manage it when we retired?

With only $15,000 in savings for either a downpayment on a house in San Francisco or for a home in the south of France, our selection was extremely limited in both places. When I thought about buying a home in France, I knew exactly what I wanted. A pigeonnier like the one we had stayed in during our first visit. And near grape vines. Another decision I had made during our first visit to the Dordogne. As we sat on the terrace of a restaurant we had happened upon. We were in Monbazillac, just outside of Bergerac. It’s the name of the village and the name of the wine, a sweet wine. Often referred to as the poor man’s Sauterne. As my husband and I shared a pression (draft beer) and our daughter sipped her citron pressé (lemonade), we drank in the vast panorama of gently rolling hills covered with rows of grapevines. Nature by itself is fine for some people, I guess, but I prefer it juxtaposed with evidence of the hand of man – stone structures and grape vines – the Perigord.

After we bought our pigeonnier, we didn’t see it for two years. When we returned, we brought our baby son with us. To celebrate his first birthday and our tenth wedding anniversary, we puttered around our ruin, scraping off plaster and pulling out rotting beams while our son napped and our daughter played with the neighbor’s kittens.

“Your roof needs repair,” the neighbor told us in French when he saw us. “If you don’t fix the roof,” he said, “the walls will collapse.”

I knew he was right. Crumbling old stone walls, sometimes with remnants of roofs that had once held them in place, are the picturesque backdrop and momento mori of the French countryside. My husband had just inherited $7,000 from an aunt he hadn’t seen in twenty-five years. It cost $7,000 to fix the roof of our pigeonnier.

The next year when we arrived, our neighbor told us that the man up the road was looking for us.

“Do you want to buy the land across from your house?” the man asked. “Papa has died.”

We hadn’t known that it was his land, hadn’t known that he had bought it to build a small house for his father, hadn’t known until that moment, just how lucky we were that his papa had died. We bought the land and the unimpeded views of sunflower fields and grapevines that it assures us. The man planted a walnut tree on the land the day he sold it to us. Each year we measured its growth on the same day we recorded our children’s heights.

A farmer came by, mowed our land with his tractor and made a neat roll of hay for his cows. Before he took the hay, we took a family photograph standing in front of it, with our pigeonnier behind us. The photograph, with the words, “Hay, Merry Christmas,” was our Christmas card that year. Our American friends understood the greeting, but didn’t recognize the house, our French friends recognized the house, but didn’t understand our greeting.

The next year, our neighbor said ‘Do you want to buy our barn?”

“Oh yes,” I said, not telling him that I had been dreaming of doing just that for 7 years.

“You don’t have to buy it now” he said. But I couldn’t wait.

That summer my husband and I worked long days, scraping off loose plaster and removing large stones from doorways and windows, stones that had been used to separate the pigeonnier from the barn. To Michelangelo, the sculptor’s job was to free the statue from the marble. That summer, like a sculptor, I freed the stones from the plaster and the openings from the stones that hid them.

By then, my husband had retired and we had begun spending summers in the Perigord, staying at gites close to our pigeonnier. The first few years, the four of us visited it together. We would putter around (Figs 1, 2) and then eat a picnic lunch on a blanket that I spread over the grass, under the fig tree.

Figure 1. Ginevra, Nicolas (in back) and Charles at Petit Bout

Figure 2. Pigeonnier before renovation

Then the children began to find excuses not to visit the pigeonnier. They complained that there was nothing to do and the pigeonnier was dirty. There was merit to their complaints. The pigeonnier and barn were dirty. There was nothing to do but clean up (and dream). And although no human had lived there for thirty years, the pigeonnier wasn’t uninhabited, pigeons made nests, raised their young, deposited their dung.

“You know, “ I told my daughter one time, “Pigeon dung is a very rich fertilizer. For centuries,” I continued, hoping to establish a link between her interest in clothes and the pigeonnier, “dung was an important part of a young woman’s dowry.”

“It’s still gross,” she said not looking up from the issue of Jeune et Jolie she was studying, “I’m not coming.”

So my husband and I slipped away every so often to visit the pigeonnier on our own. We wandered around discussing where the kitchen would be and how many bathrooms we needed; where to put our bedroom and how to create a private terrace.

Finally, after 15 years, we had saved up enough money to transform our ruin into a home. We met a young architect and showed her around, ducking as the pigeons flew overhead, feeling our way in the dark as my husband opened the shutters. We explained that what we really wanted was indoor plumbing and no pigeons.

The work was scheduled to begin soon after we left in August. Throughout the fall and winter, we received weekly emailed photos, of windows being created and walls reinforced, of sous sol heating being laid and shutters being installed. (Figs 3, 4) And yet, as one year ended and a new one began, I wondered and I worried. Would I recognize our little ruin? For so long, its existence had been a source of solace and succor as we struggled with the realities of making a life and earning a livelihood six thousand miles away in California. Unfinished, our ruin had remained an ideal, a tabula rosa, pure in its promise of perfection.

Figure 3. Renovations in progress

Figure 4. Fireplace being cleaned

Finally, we were back. My husband and I dropped the children off and drove to our new/old home. I flew out of the car and into the pigeonnier clutching the photo I had gazed upon for fifteen years. I rushed over to that window, flung open the shutters and stepped back. The same light streamed in and the same magical tranquility was waiting to embrace me. (Fig 5)

Figure 5. The sun still streaming in

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.