Art as Life, Life as Art.

SOPHIE CALLE. IT'S UP TO YOU, DARLING. Musée Picasso.

Before Sophie Calle took over the Musée Picasso, the designer Paul Smith offered a quirky look at Picasso’s work. Smith’s exhibition was exuberant, refreshing and essentially polemic-free. It was a celebration of color and line and pattern. To appreciate Smith’s exhibition, visitors needed only a sense of fun. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1. Picasso exhibition by Paul Smith at Musée Picasso

Calle’s exhibition is completely different. It suggests how one might consider, contemplate the narrative of one’s own life. The Musée Picasso press kit describes Calle as “a conceptual artist, photographer, video artist and even detective, (who combines) text and photography to nourish a narrative that is her own. … Sophie Calle sometimes blurs the boundaries between the intimate and the public, reality and fiction, art and life. Her work meticulously orchestrates an underlying reality - her own or that of others - while leaving room for chance.”

This exhibition demands a lot of time and considerable effort. One American critic suggests that Calle has never really caught on in America because her work requires so much reading, so much work. This final exhibition celebrating the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death, ironically has more to say about death than about Picasso. Clever and witty and thoughtful, the exhibition is Calle’s retrospective rather than Picasso’s, although interwoven throughout are riffs on things Picasso said, things people said about Picasso.

When asked how she feels about filling the Musée Picasso with her own work, Calle recounts her mother’s reaction to her first major exhibition outside of France. (Fig 2).“When I exhibited at MoMA (1992) next to the Magrittes and the Hoppers, (my mother) told me “You really fooled them.” as though I had managed to sneak my way in.” Sophie initially declined the Musée Picasso’s offer to mount an exhibition there. Eventually, she changed her mind, it was a way to get out of the house during the pandemic. Even though her mother has been dead for more than 15 years, how her mother would have responded still swirls around Calle’s head. She can hear her mom saying “‘Aren’t you scared? Aren’t you ashamed? Why you?’ I imagined her bursting out laughing and telling me: ‘Well, that just takes the cake!”’

Figure 2. What Sophie Calle’s mother said when she saw her daughter’s work at MoMA, New York

When Calle is asked how Picasso would have responded to her taking over his museum, she sometimes replies with this story. When she was 6, she drew a picture. (Fig 3) Her father had it framed and her grandmother declared her another Picasso. Sometimes she says the answer is in the title of the exhibition, “It’s up to you, my darling,” the title of a 1941 thriller written by English author, Peter Cheyney. (Fig 4) Sometimes she says “I decided that (Picasso’s reaction) would be benevolent, I don’t want to come and squat in a hostile place…”

Figure 3, Drawing by Sophie Calle, age 6. Framed by father, called a Picasso by grandmother

Figure 4. A toi de faire ma mignonne, Peter Cheyney, 1941

As a retrospective, this exhibition combines works that Calle has already exhibited with ones she created specifically for this venue. On the ground floor Calle offers a record of her first few visits to the museum. The first was during confinement, and the museum was closed. Picasso's paintings were covered with paper to protect them from the sun and dust. (Fig 5) She took photos of these phantoms. During a subsequent visit, some of the paintings were out on loan. This time she asked museum security guards to describe the works to her. The paintings are back now but Calle has covered them with translucent white fabric onto which she has printed the guards’ descriptions. The paintings may be physically there, but you can only see them through someone’s else eyes, someone else’s description.(Fig 6)

Figure 5. PIcasso paintings protected during pandemic, photos by Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

Figure 6. The Swimmer, Picasso veiled and described by guard, Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

It’s an echo of an exhibition which Calle created at the Isabelle Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, after the 1990 theft of some of that museum’s most important works, a Vermeer among them. Calle had asked guards and curators at the Gardner what they remembered about the stolen paintings. Their words became her art work.

On the next floor is a riff on Picasso’s Guernica. As with so many things she does, the piece is in response to something Calle read. In this case, it was Arshile Gorky’s suggestion to a dozen or so fellow artists that they create a work in response to Guernica. Nothing apparently came of Gorky’s proposal. That is until Calle finally heeded Gorky’s 75 year old call. Her Guernica is the same dimensions as Picasso’s (nearly 11.5 feet by 25.5 feet). And is made up of 200 or so photographs, objects and miniatures from her own collection of works by other artists, like Damien Hirst and Cindy Sherman. (Figs 7, 8, 9) Calle’s piece is not a political statement but an acknowledgement of the importance of Picasso’s work and a sense of its actual size.

Figure 7. Riff on Picasso’s Guernica, Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

Figure 8. Sophie Calle’s riff on Guernica, detail drawing of mouse

Figure 9. The mouse, Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

On another floor, three rooms are dedicated to the sense of sight. Calle has exhibited these works before. Here they have a Picasso connection. Picasso once said that painting is a blind man’s job. A painter paints not what he sees, but how he feels about it, what he tells himself about what he has seen. And this, from an anecdote recounted by Jean Cocteau. In Avignon, Picasso once saw an old, half-blind painter and his wife. She was standing, looking through binoculars at a castle in the distance. He was sitting, at his easel, brush in hand. As she described what she saw, he painted what he heard. Finally this. Calle found a letter in Picasso’s personal archives at the Museum, it was from the Association d’aide aux artistes aveugle (AAAA) asking Picasso to donate a drawing so they could sell it at auction to raise funds for blind artists. Not knowing how he responded, Calle convinced the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso to put a Picasso ceramic up for auction and donate the proceeds to AAAA. (Figs 10, 11)

Figure 10. Announcement of Auction for Ceramic by Picasso, Musée Picasso

Figure 11. Ceramic by Picasso to be auctioned, proceeds to go to AAAA

One of the three rooms is called, “Voir la mer.” (Fig 12) Calle produced videos of poor Turkish people who live just miles from the sea but who have never seen it, being shown the sea for the first time. Calle calls this her “first silent work.” “They were too moved [for me] to ask questions,” she says. “And what can you say about the sea?…The horror was that they’ve never seen the sea, not what they think of it.”

Figure 12. Voir la Mer, people seeing the sea for the first time, Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

In "Les Aveugles” (Fig 13) Calle asked people who were blind from birth to describe their idea of beauty. There are photos of the people she interviewed, wall text describing their idea of beauty and a picture, chosen by Calle, of what they described. In "La dernière image,” the most tragic of the rooms, are people who had lost their sight. Calle asked them and shows us, the last thing they remember seeing.

Figure 13. Les Aveugles (the Blind) Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

The third level begins with an 11 minute video called “Pas pu saisir la mort” (Couldn’t catch death), a memorial to Calle’s mother, first screened at the 2007 Venice Biennale. (Fig 14) Initially taken so she could be with her mother when she died even if she wasn’t physically in the room, Calle decided to follow her Venice curator’s advice and make it a work of art to be shared publicly.

Figure 14. Sophie Calle’s mother on her death bed, Video by Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

Nearby a photo of her mother, as a young woman, is accompanied by a caption from her diary, “No use investing in the tenderness of my children, between Antoine’s placid indifference and Sophie’s selfish arrogance! My only consolation is she is so morbid that she will come visit me in my grave more often than on Rue Boulard.” (Fig. 15)

Figure 15. Rachel Monique (Sophie Calle’s mother) diary page complaining about her daughter

Calle explains, “She gave me the diaries, she knew the camera was there….I spoke to my mother about the Biennale ... She was horrified about not being there. I thought the only way I can make her be there is if she's the subject.” For Calle who was very close to her mother, filming her dying was therapeutic, it ‘helped me more than it weighed me down, because all of a sudden we had a project together’.

With both of her parents dead, the exhibition segues into Calle’s own demise. Specifically, since she had no heirs, what is going to happen to all of her stuff when she dies. She came up with a plan, a sort of dress rehearsal, if you will, which the Musée Picasso paid for, of course. “Picasso saw death in completion and refused to make his [last] will and testament, ’That attracts death,’ he would say. I prefer to play with it, but maybe it comes from the same fear.”

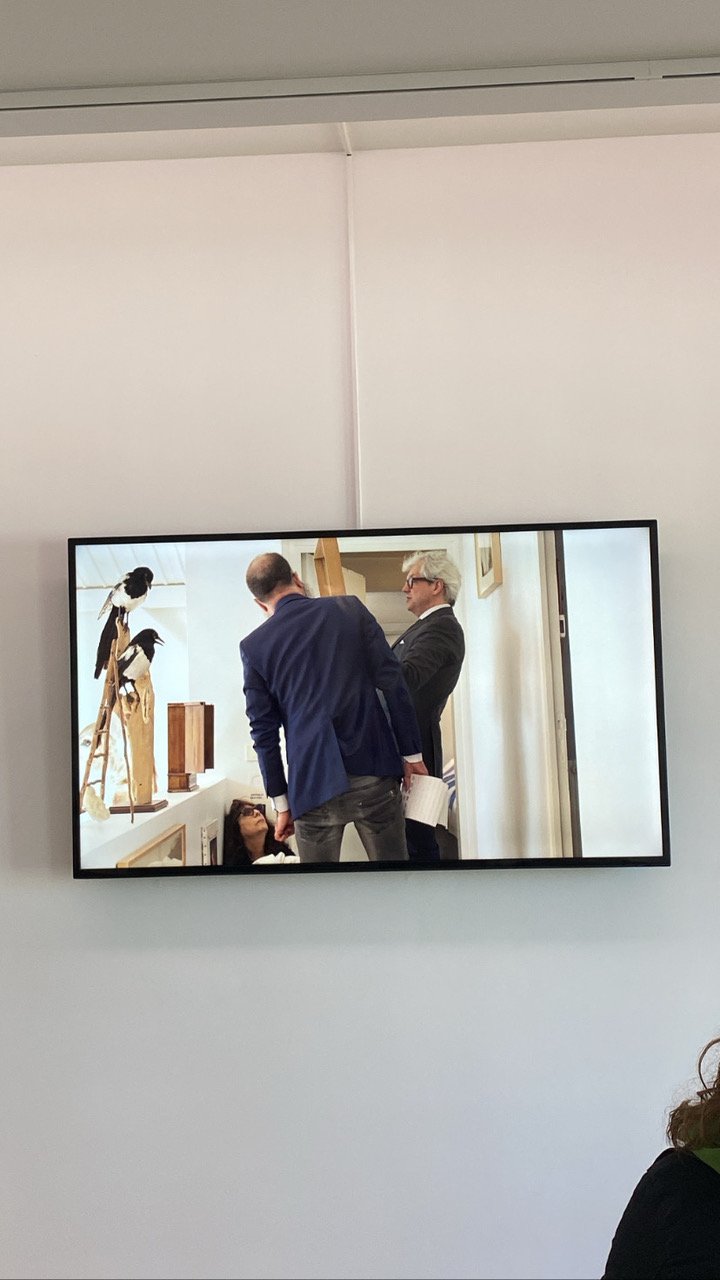

She asked the auctioneers at Drouot to “stage my nightmare, to value the possessions in my house … and to draw up a descriptive inventory of my moveable assets, but not an estimate.” The video of the Drouot experts at her home and studio is a hoot as they valiantly try to describe what they are examining. Calle did not do what any of us with any sense would do - that is, she didn’t leave and let the experts get on with their business. Instead, she hung around and just keeps popping up. In the bathtub. On the piano. Under a desk. (Figs 16,17,18)

Figure 16. Sophie Calle in her bathtub, video, Musée Picasso

Figure 17. Sophie Calle on piano, video, Musée PIcasso

Figure 18. Sophie Calle under her desk, video, Musée Picasso

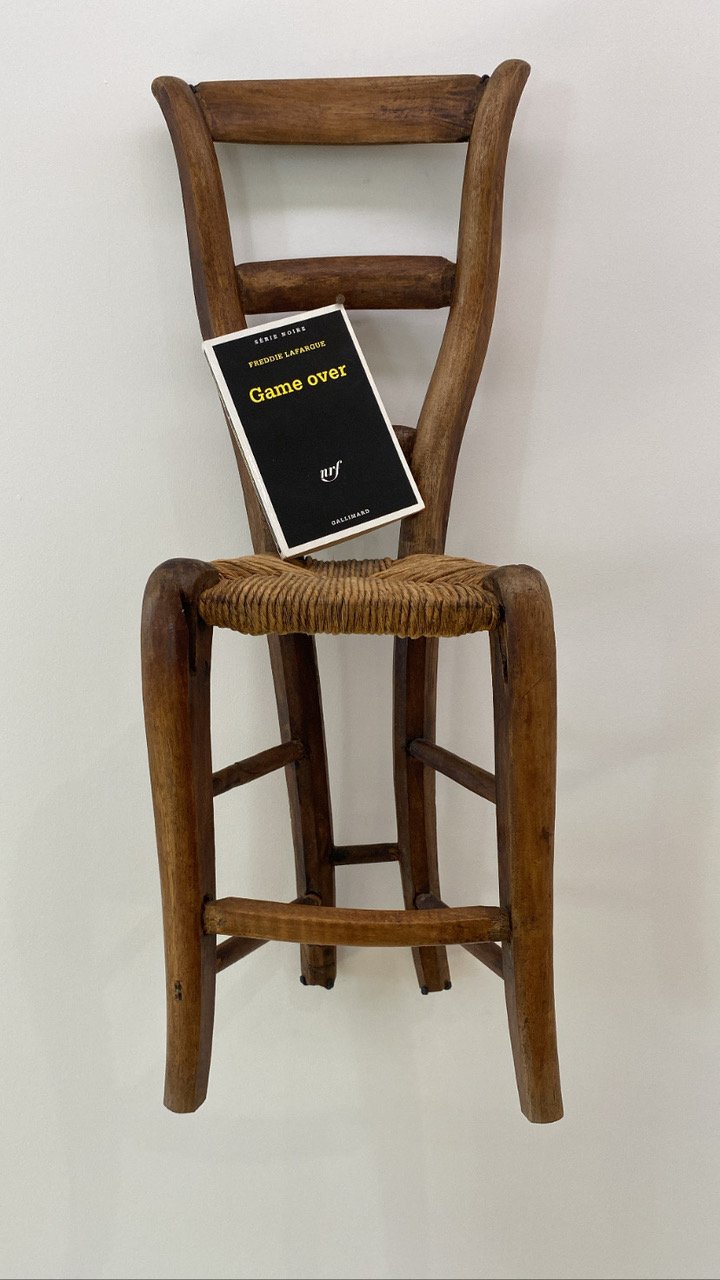

After the fun of watching this video, you go into the next room where most of the stuff that you have just seen in situ, is on display. (Figs 19, 20) Arranged as if in an auction house salesroom. And the catalogue with notes Drouot appraisers took when they assessed the pieces. (Fig 21) Here’s the Picasso link, according to Calle, “Picasso wished to show what laid behind his paintings, I wanted to tell the stories behind some of my personal belongings.”

Figure 19. Sophie Calle’s stuff, Musée Picasso

Figure 20. Sophie Calle with her stuff at Musée Picasso

Figure 21. Page of Auction Catalogue of Sophie Calle’s stuff prepared by Druout, Musée Picasso

The top and final floor offers an overview of Sophie Calle's projects. The Completed Ones and the Ones Abandoned. (Fig 22) Both are presented in the form of thrillers with titles taken from the artist’s works.

Figure 22. Description of Projects - Completed and Abandoned

I want to give you an idea about all the thought that goes into one of Calle’s pieces. I’ll take as an example a work that she created for the 2007 Venice Biennale at which she represented France. The impetus was a break-up email she had received from her boyfriend two years earlier. According to Calle, "The idea came to me .. two days after he sent it. I showed the email to a close friend asking her how to reply, and she said she'd do this or that. The idea came to me to develop an investigation through various women's professional vocabulary…After one month I felt better.… It worked. The project had replaced the man.” What started out as therapy became art.

It was the last sentence of the email, "Take care of yourself.” that offered Calle a path to closure. She took care of herself by asking “107 women…chosen for their profession or skills, to interpret the email. To analyze it. Comment on it. Dance it. Sing it. Dissect it. Exhaust it. Understand it for me. Answer for me. It was a way of taking care of myself.”

Calle’s piece is comprised of photographs of all 107 women reading the email. Next to each is a photo or video of their responses. A Copy Editor corrected the ex-lover’s grammar and syntax. An Etiquette Consultant mocked his manners. A Markswoman put bullet holes in the letter. A crossword-setter made a crossword puzzle out of it. A Forensic Psychiatrist called him a ‘twisted manipulator’. Jeanne Moreau performed it. (Figs 23, 24, 25)

Figure 23. “Take Care of Yourself” Sophie Calle, 2007 Venice Biennale

Figure 24. Copy Editor corrected ‘Take Care of Yourself’ Sophie Calle

Figure 25. Take Care of Yourself, Crossword Puzzle, Sophie Calle

As Angelique Chrisafis wrote, (Guardian, 2007) Calle said that her biggest worry as she developed the piece was that her ex-lover would ask for a reconciliation. And if she accepted, it would be the end of the piece. Was Calle’s ex-lover surprised about her piece? “He said 'take care of yourself', he knows how I take care of myself, he knows what my method is.”

When criticized for mining her life to create her art, Calle’s answer is this: ”Love, life and death - all of that is… material for artists. It amuses me because people often say, doesn't it bother you to show your private life? I say, well if you ruled out private life, you would have to eliminate all poetry….Victor Hugo, Baudelaire and Verlaine …”

It reminded me of what Taylor Swift said when she was accused of singing about her love life. She called it sexist. She pointed out that nobody criticizes Ed Sheeran or Bruno Mars for using their love lives in their songs. They do it, so does she. Here’s a verse of the song she wrote and sang when she hosted Saturday Night Live in 2009 (Fig 26), “You might think I’d bring up Joe; The guy who broke up with me on the phone; but I’m not going to mention him; IN MY MONOLOGUE; Hey Joe! I’m doing real well; Tonight I’m hosting SNL; But I’m not going to brag about that IN MY MONOLOGUE.”

Figure 26. Monologue Song, Taylor Swift, SNL, 2009

Mary Kaye Shilling, (NYTimes, 2017) discussed some of the ideas I have been thinking about ever since I first saw this exhibition. Calle’s detractors say that “her voyeurism and life-as-art approach (are) the definition of TMI” (too much information). That her work is “exploitative, invasive, silly… crazy.” For others (like me), Calle’s “freewheeling imagination, coupled with an ability to turn emotional chaos into compelling narratives, is thrilling. So too is her disregard (for) gender limitations… and indifference to what is considered appropriate.”

As cerebral and text reliant as her work is, one could posit that Calle “has predicted our current cultural moment, from the staged intimacy of reality TV and the faux intimacy of social media…” Calle is not ‘into’ social media, she “has no interest in or familiarity with virtual sharing.” The intimacy of Calle’s work may make you cringe, but it isn’t raw, it’s refined. It isn’t life lived, it’s life curated. It’s what makes Calle’s life art, and Taylor Swift’s life songs.

At the very end of the exhibition is Sophie Calle’s office. You are welcome to knock on the door, she will answer if she is there. (Figs 27, 28 )

Figure 27. Sophie Calle answering her door, October, 2023, Musée Picasso

Figure 28. End of exhibition, Sophie Calle, Musée Picasso

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.