Three Score & Ten Days

Van Gogh in Auvers, Pissarro in Pontoise

Moi and le train.

We are traveling out of Paris today, to Auvers-sur-Oise and Pontoise. The first to walk in the footsteps of van Gogh, the second to pause where Pissarro and fellow impressionists painted. And while we’re in Auvers, we’re going to see a sound and light show, one that is interesting and informative, persuasive, though definitely not pedantic. Auvers and Pontoise are only ten minutes from each other and only 35 km from Paris (half the distance of Giverny). You could visit both in one day, but why not make a weekend of it and savor the experiences. Because when you are able to visit these villages it will be when this country and the world are open again. And you will be able to punctuate your wanderings with a café mid morning and a verre later in the afternoon, and of course there will be meals to anticipate and enjoy. The way it used to be. The way it will be again. Soon. Though not as soon as we had thought. We’ve just been told that the earliest this country will begin to reopen is mid-May. And so we go ….. haltingly, hesitantly, hopefully, towards what will happen next.

Figure 1. Vincent Van Gogh, self portrait, 1890, Courtauld Institute, London

We begin with Vincent van Gogh, who arrived in Auvers on May 20, 1890. He had been discharged only four days earlier from the asylum at Saint-Remy, where he had stayed for a year following a well known altercation with fellow artist Paul Gauguin and an even better known episode with his own severed ear. (Figure 1) At both Arles and St Remy, Vincent had been prolific, painting some of his best known and most beloved canvases. (Figure 2) But he was ready to leave the south of France, ready to be closer to his brother, Theo, who lived in Paris with his young wife, Jo and their infant son, Vincent.

Figure 2. Sunflowers, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

It was Camille Pissarro, living then in Pontoise, who suggested to Theo that Vincent “come and live in Auvers, because of the light and Doctor Gachet.” Dr. Gachet was a homeopathic doctor, amateur painter and a talented engraver who counted among his friends many of the painters Vincent admired and knew. In fact, Dr. Gachet had taught Pissarro and Cézanne the art of engraving. Gachet supported Impressionist artists by buying their work and accepting their work in lieu of payment for his services, as he did with Vincent.

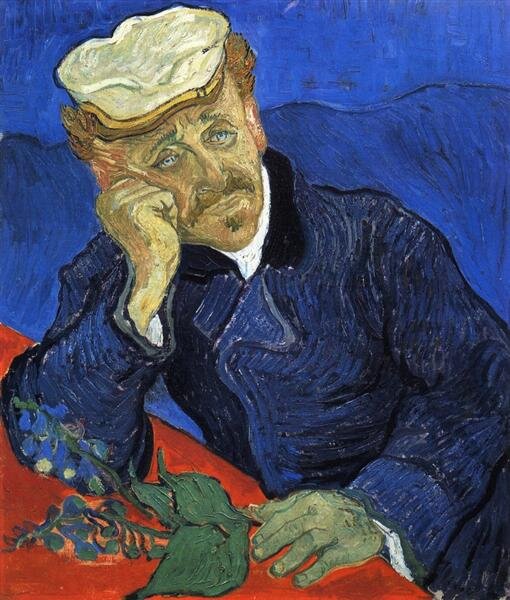

Van Gogh followed Pissarro’s advice and went to Auvers to be cared for by Dr. Gachet. At first Vincent wasn’t convinced that he was any crazier than the good doctor was, telling Theo that Gachet was: "sicker than I am, I think, or shall we say just as much”. Their relationship improved and Vincent spent a lot of time at Gachet’s home. He painted the good doctor’s portrait several times. One of those portraits, Gachet seated at a red table holding a branch of foxglove (digitalis) is now at the Musée d’Orsay. (Figure 3) The museum’s catalogue describes the portrait this way “He (Gachet) was no ordinary model and is portrayed in a melancholy pose reflecting "the desolate expression of our time," as van Gogh wrote.

Figure 3. Dr. Gachet, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Figure 4. Bedroom in Arles, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

While in Auvers, Vincent lived in town, on the main street, at the Auberge Ravoux which is still there but which was closed when I was there. You can visit Vincent’s room but there is not much in it that would remind you of Vincent, except perhaps its size, as tiny as the bedroom in Arles that he immortalized. (Figure 4)

Vincent lived in Auvers for 70 days and during those 70 days he painted 70 canvases. Although none of the 70 paintings is still in Auvers, there is a lot to do and see. You can wander around the village and nearby countryside, bumping into views that Vincent captured, aided by panels placed in front of those views, the fields and the farms; the village houses and the Mairie, too, decorated with bunting for the Quatorze Juillet. (Figure 5, Figure 6)

Figure 5. Mairie, Anvers-sur-Oise, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890, private collection

Figure 6. Mairie, Auvers sur Oise with panel in front with van Gogh’s painting

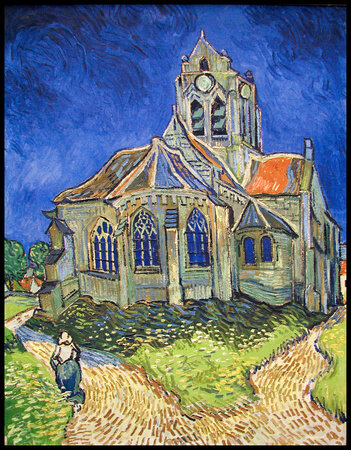

His painting of the village church is one of his most famous and it is especially poignant since Vincent and Theo are buried in the adjoining cemetery. (Figure 7, Figure 8) The cause of Vincent’s death was, for years, assumed to have been by suicide. Recently some historians have begun to dispute that assumption. Their theory is that Vincent was walking in a field, as he often did, canvases and paints slung over his shoulder, as Issip Zadkine memorialized him in a statue in the garden in front of the tourist office. (Figure 9) It was in the field that Vincent encountered the 16 year old René Secrétan, a summer visitor who was known to have taunted the artist. René had a pistol and accidentally (?) shot the artist who then fled to his room at the inn, gravely wounded. The village doctor and Dr. Gachet were called in. They did their best to help him, but with the tools and skills they possessed, there wasn’t much they could do. Theo rushed down from Paris and was at his brother’s bedside when Vincent died two days later.

Figure 7. Church at Auvers-sur-Oise

Figure 8. Church at Auvers-sur-Oise, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Figure 9. Statue of Vincent Van Gogh, Ossip Zadkine, 1955, Auvers-sur-Oise

This sad story just gets sadder. Theo died just 6 months after Vincent did, at age 33 (Vincent was 37) of complications from syphilis. It was an awful death, dementia paralytica, an infection of the brain. (Figure 10) Jo, Theo’s widow was left with virtually all of Vincent’s paintings and drawings and all of the letters the brothers had exchanged over the years. It was also left to Jo to figure out what to do with all those paintings, to figure out how to promote her brother in law’s talent. It was Jo who transformed a virtually unknown painter who had sold only a few canvases before his death into the artist Vincent about whom books, plays and movies have been written. For whom an entire museum is dedicated, which you have probably visited in Amsterdam. If you are interested, here is a link to an excellent NYTimes Magazine review of a fascinating book on this subject that has recently been published: nytimes.com

Figure 10. Vincent Van Gogh and Theodore Van Gogh tombstones, Auvers-sur-Oise

You can visit particular sites where Vincent painted, like the home and garden of Dr. Gachet, which Vincent painted several times. The above mentioned portrait of Dr. Gachet was painted in his garden. Van Gogh painted two portraits of Gachet’s daughter, Marguerite who was 19 when Vincent arrived in Auvers. Some have suggested an attraction between them which Dr. Gachet thwarted, but there is no evidence to support that claim. However, Vincent’s portrait of Marguerite playing the piano in her home, hung on her bedroom wall for 44 years, until she died, unmarried, in 1934. His portrait of ‘Marguerite in the Garden,’ (Figure 11) now at the Musée d’Orsay shows the young woman wearing a straw hat and light dress, standing gracefully like a pillar of calm set within the swirling waves of white flowers and undulating gray and green trees that surround her.

Figure 11. Marguerite in the Garden, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Figure 13. Le Botin replica. River Oise, Auvers-sur-Oise

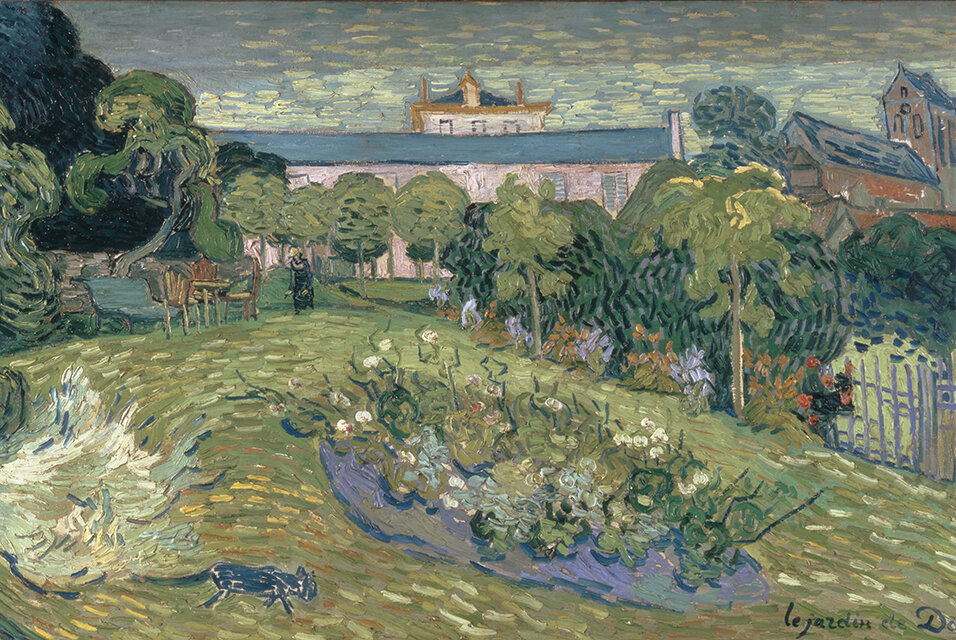

You can visit another site that Vincent painted, the garden of the home/studio of Charles Francois Daubigny. (Figure 12) Have you ever heard of Daubigny? He was born in Paris in 1817, into a family of painters. Travels to Rome as a young man transformed him into a landscape artist, more specifically, a painter of river scenes. Daubigny was a plein air painter, that is he painted out of doors. Indeed, a few years before he moved to Auvers in 1860, obsessed as he was with painting river scenes as he found them, he bought a boat and transformed it into a floating studio so he could be as close as possible to his subject. So he could find and maintain the best positions from which to capture the effects of natural light. At the edge of the River Oise, bobbing up and down is a replica of Daubigny’s studio/boat, the Botin (little box). (Figure 13).

Figure 12. Daubigny’s Garden, Auvers-sur-Oise, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890, Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel

At first Daubigny lived and worked in Paris and spent his summers in Auvers. When he bought a plot of land for a home/studio, he became the first artist to settle in Auvers. In 1863, for Daubigny’s daughter’s birthday, he and a few friends, among them Corot and Daumier, decorated her bedroom with scenes from fairytales like ‘Little Red Riding Hood.’ (Figure 14) Having had so much fun with that, they went on to decorate other rooms with scenes from nature. The frescoes survive and they are lovely.

Figure 14. Maison Daubigny, daughter’s bedroom, Auvers-sur-Oise, 1863

Daubigny may not be a household name now, but everyone knew him back in the day, when his kindness to fellow artists was much appreciated. Vincent knew his work and admired it greatly, feeling a kinship with Daubigny even before he became a committed artist. Vincent wrote this from Brussels to his brother Theo when he learned of Daubigny’s death in 1878, ”Daubigny is dead.… it must be a good thing, while dying, to be conscious of having done really good things… and to leave a good example to those who follow us.”

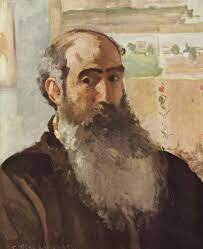

Figure 15. Camille Pissarro, self portrait, 1873, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Let’s wander over to Pontoise, now, to Camille Pissarro country. (Figure 15) You’ve heard of Pissarro, right? Well, just in case you’ve forgotten. Pissarro was born in 1830 on the island of St. Thomas (now the U.S. Virgin Islands, then was the Danish West Indies). Have you read Alice Hoffman’s book about Pissarro’s mother, The Marriage of Opposites? It’s a good read, especially if you like historical fiction. Pissarro went to boarding school in France from age 12 - 17 and lived in Venezuela for a couple of years after that. At 25, he returned to France, first to Paris and then to Pontoise where he settled in 1872. He invited Cézanne to join him, which he did, as did Degas a few years later and Gauguin a few years after that. And we know he recommended Auvers and Dr. Gachet to van Gogh. As at Auvers, there are panels at the locations that artists painted their well known scenes. It is lovely to wander around town and along the banks of the Oise, finding the panels and looking at the same views the artists did.

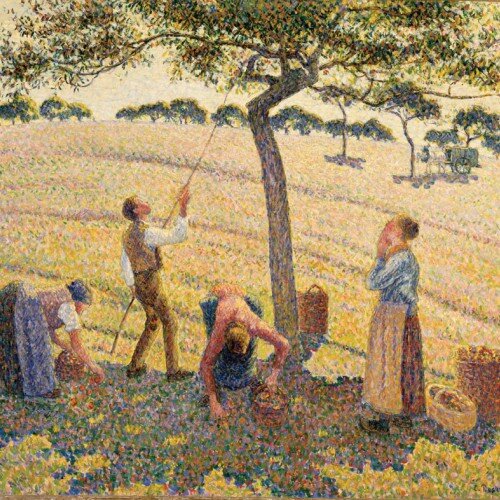

Figure 16. Apple Harvest, Camille Pissarro, 1888, Dallas Museum of Art

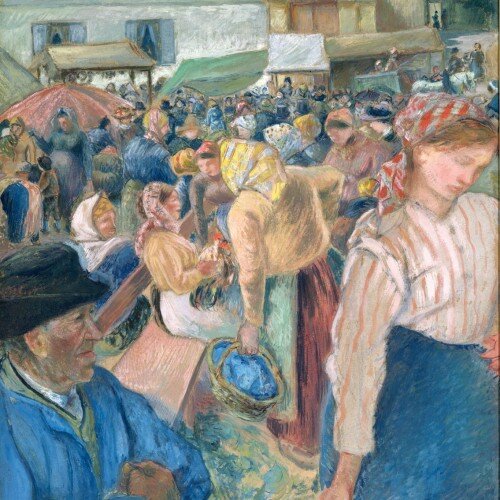

Pissarro has traditionally been portrayed as the patriarch of Impressionism. Who befriended all and helped many. Who painted "what he saw.” The art historian Richard Brettell refutes the final bit, suggesting that Pissarro was detached from the reality of Pontoise, especially the lives and livelihoods of its inhabitants. Which is interesting because I saw a really lovely exhibition a few years ago at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco entitled ‘Pissarro’s People’. There were portraits of the artist’s friends and family to be sure, but more interesting, at least to me, were the genre scenes of anonymous people working in the fields (Figure 16) or shopping at the weekly marché.(Figure 17) That exhibition catalogue contended that Pissarro’s paintings of townspeople and farm workers “stress their individuality rather than their mythic qualities, which so preoccupied Millet, his predecessor in the agricultural tradition.” (Figure 18) But, according to Brettell, Pissarro’s concern was with structure rather than appearance. His pictures analytic compositions made up of components he re-assembled from the studies he had made directly from nature.

Figure 17. Market Place, Camille Pissarro, 1882. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Figure 18. The Gleaners, Jean-François Millet, 1857, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Which is interesting because Pissarro and Paul Cézanne were very close. And it was Cézanne who broke away from Impressionism because the paintings focuses on light and atmosphere, not structure. Cézanne moved to Pontoise in the spring of 1872 to work alongside Pissarro, to paint directly from nature with Pissarro. (Figure 19, Figure 20) But Cézanne failed to become an Impressionist, it wasn’t in him. His concern for structure took him along a different path. Although if Brettell’s reading of Pissarro is correct, they shared the same interest in structure, they simply followed different paths to achieve it. But Cézanne has always been credited with paving the way for the development of Cubism in the early 20th century.

Figure 19. L’Hermitage, Pontoise, Camille Pissarro, 1867,Guggenheim Museum of Art, New York

Figure 20. L’Hermitage, Pontoise, Paul Cezanne, 1881

Figure 21. Thousand And One Nights, Georges Manzana Pissarro

Pissarro’s sons, Lucien, Georges, Ludovic-Rodo and Félix all became painters. When I visited the Pissarro Museum last fall, in addition to the permanent collection of paintings by Pissarro and his family and his friends, there was a temporary exhibition of works by his son George on The Thousand and One Nights Arabian Nights which was quite beautiful. (Figure 21)

I promised you a sound and light show. So, here it comes. When Barb Keeney and I first visited Auvers, we walked up to and then explored the grounds of the gorgeous Chateau d’Auvers. Built in 1635 for an Italian businessman, it was purchased by a Frenchman 70 years later, who transformed it from an Italianate palazzo to a French chateau. The gardens are a mix of Italian Renaissance, French formal and English wild. (Figure 22) And there is a 17th century nymphaeum, (Figure 23) a small artificial cave decorated with pebbles and shards of glass as well as mussel, abalone and pink conch shells.

Figure 22. Chatea d’Auvers, Auvers-sur-Oise

Figure 23. Nymphaeum, Chateau d’Auvers, Auvers-sur-Oise

Figure 24. Klimt Sound & Light Show, Atelier des Lumières, Paris, 2018

Barb and I didn’t get to the sound and light show at the Chateau d’Auvers in Auvers-sur-Oise, but you shouldn’t miss it. In Paris, I have seen all of the sound and light shows at the Atelier des Lumières since Bobby Stepp and I saw the first one in 2018, featuring the artist Gustav Klimt. (Figure 24) The experience was a lot kaleidoscopic, a little psychedelic (the show, not Bobby). If you are looking for immersion into an ever swirling, changing, dynamic series of scenes and patterns, on the walls and on the ceiling and on the floor, too, then you will be happy. But if you are hoping to learn about the artists whose works are manipulated and transformed in these shows, then you may be disappointed because I don’t think you will know any more about any of them after the experience than you did before it. You may not even recognize their paintings when you browse in the gift shop, through which you must pass on your way to the exit (thank you Banksy). But as an experience qua experience, it is fun and and it is fine. Salvador Dali and Antoni Gaudi are coming next, so get vaccinated and get over here.

The sound and light show at the Chateau d’Auvers, entitled, “Vision Impressioniste, Naissance et Descendance” (Impressionist Vision, Birth and Progeny) which opened in 2017 is a circuit of eight distinct spaces.

The Birth of Impressionism is the title of the first and biggest space and the one most like the Atelier des Lumières, filled with an ever changing array of large screen projections of paintings by the Impressionists from Manet and Pissarro, to Renoir, Monet and Morisot and of course van Gogh. (Figure 25) The biggest difference? At Atelier des Lumières, the sound track is music. At the Chateau d’Auvers the soundtrack is the words of artists, art critics and art dealers, taken from original letters, testimonies and newspaper articles. Photographs of the artists and their milieu pop up on walls and artists’ signatures appear on the floor. There is the same sense of joyful, playful abundance as at the Atelier, but here your experience is enhance with contextualized information.

Figure 25. Sound & Light Show, Chateau d’Auvers, Auvers-sur-Oise

Figure 26. The Cliffs at Le Pouldu, Emile Bernard, 1887

The three final spaces are dedicated to what happened after impressionism. First are examples of some post Impressionist movements like pointillism, cloisonnism, synthetism (Figure 26) and symbolism. Cézanne, who had painted in Pontoise with Pissarro, has a space of his own. Geometric shapes are superimposed upon a landscape painting by Cézanne, Les carrières de Bibémus, (Figure 27) the painting considered to be the progenitor of Cubism. The geometric shapes, we are told, explain Cézanne’s relationship to perspective and depth and trace how Picasso and Cubism (Figure 28) followed on from that.

Figure 27. Les carrières de Bibémus, Paul Cezanne, 1895

Figure 28. Brick Factory at Tortosa, Pablo Picasso, 1909

The final space establishes the link between Monet and abstract expressionists like Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko and Joan Mitchell. Monet, like Cézanne, had painted in Pontoise with Pissarro. Indeed Pissarro urged him to settle there, but Monet chose a location a little farther away from Paris, Giverny. I saw al really interesting exhibition a few years ago at the Musée de l’Orangerie where you will find Monet’s Waterlilies. It traced the link between Monet and Abstraction and included two short films, one of Monet painting, the other of Jackson Pollack painting, an interesting and convincing juxtaposition. (Figure 29, Figure 30) At the Musée Marmottan-Monet, home to Monet’s last paintings, a contemporary artist is regularly invited to create works in dialogue with Monet’s own. In this way, Monet’s influence continues.

Figure 29. Claude Monet’s Japanese Bridge, Giverny, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1918-1926

FIgure 30. Free form, Jackson Pollack, MOMA, 1946

Come to Paris when you can and take a day or overnight trip to Auvers-sur-Oise and Pontoise. They aren’t far but they are just far enough for you to get a sense of the beautiful countryside around the beautiful city of Paris, the same journey the Impressionists took.

Copyright © 2021 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved